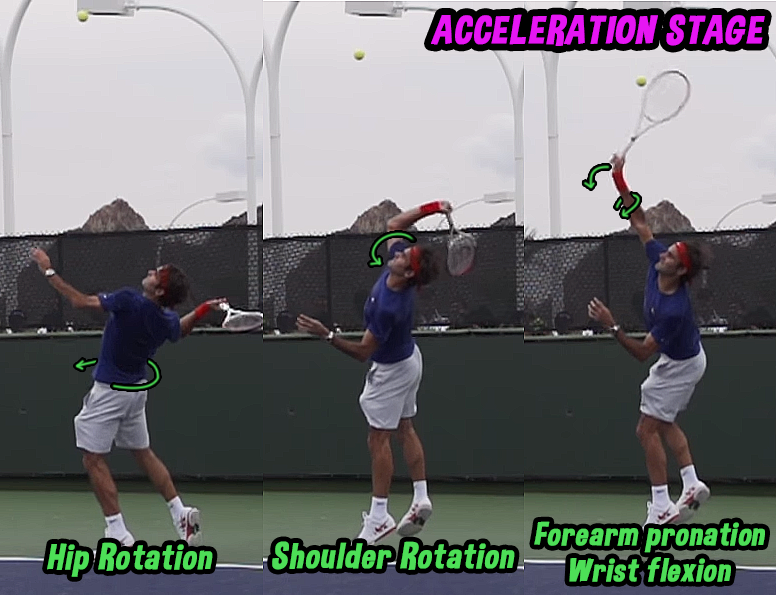

Acceleration Stage:

Vigorous acceleration of the contact arm defines the acceleration stage, as PE stored during preparation is translated to a fast serve (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011). The body undergoes a corkscrew motion as the angular velocity of successive limb segments sequentially increases until contact (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011). As displayed in Figure 5, the hip internally rotates, followed by trunk and shoulder internal rotation, forearm pronation and wrist flexion (Elliott, 1988).

To initiate this movement, the individual must overcome their limb’s MOI, I = mk2 (Blazevich, 2017). Ultimately, if the radius of gyration (k) decreases, so will the MOI. This is crucial because angular acceleration is inversely proportional to inertia α=τ/I (Blazevich, 2017). Therefore, the individual will contact the ball with greater angular velocity provided the MOI is less. Hence, as evident in Figure 5, the angle of elbow flexion and internal rotation of the shoulder is manipulated, reducing the proximity of the limbs to the axis of rotation, decreasing MOI and increasing angular acceleration, ensuring high velocity upon contact.

However, simply increasing angular velocity will not ensure a powerful serve; under this perspective the significant >135° of elbow flexion recorded upon ball contact detrimentally impacts force production (Gordon & Dapena, 2006). Instead, highlighted in Figure 6, professional players contact the ball at their throw’s peak, maximising arm length (Vaverka & Cernosek, 2016). The linear velocity of the ball following contact is attributed to both angular velocity (ω) and arm length (r), v=rω (Blazevich, 2017). Therefore, to ensure a forceful serve the player must maximise torque, a measure of force imparted a certain distance from the axis of rotation (Blazevich, 2017). Simply, torque increases with a larger radius of gyration and resultant MOI, τ=α.I (Blazevich, 2017). Thus, the individual must also ensure maximal torque upon contact to promote fast ball speed.

Consequently, MOI of the contact arm must first be reduced, increasing angular acceleration, and subsequently increased, enhancing torque production. This manipulation relies upon the law of the conservation of momentum, whereby momentum in a closed system remains constant (Blazevich, 2017). Angular momentum (H=I.ω) is a product of MOI and angular velocity; therefore, provided angular momentum is constant or increasing, if MOI is decreased during acceleration commencement, the angular velocity of the arm shall increase drastically (Blazevich, 2017). However, as the arm lengthens during contact, both the angular velocity and radius of gyration are maximised to impart the greatest force possible. Resultantly, both acceleration and torque can be maximised under this principle, ensuring a fast serve.

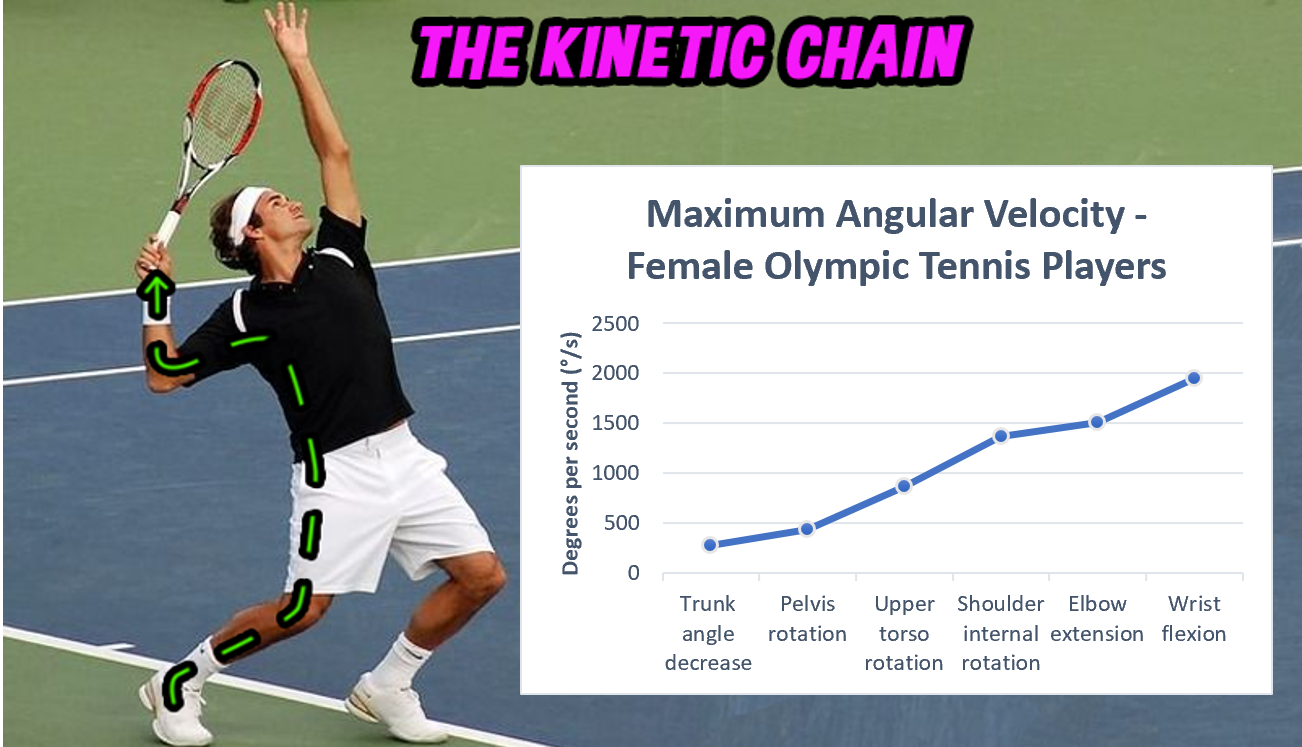

Momentum is conserved throughout the entire kinetic chain: defined as the successive sequence of moving parts or levers contributing to the serve (Elliott, 2006). This sequential movement is an example of a throw-like movement, as the momentum generated through acceleration of proximal segments is transferred distally (Blazevich, 2017). Resultantly, angular velocity increases sequentially before contact per Figure 7, with the wrist reaching speeds of 1950 ± 510 deg.s-1 (Fleisig, et al., 2003). Angular momentum (H) is a product of MOI and angular velocity; therefore, as momentum is conserved, successive limb segments periodically decrease in MOI due to decreasing weight and radius of gyration, exhibiting increased angular velocity (Blazevich, 2017). Roberts & Azizi (2011) highlighted this throw-like movement also promotes the greatest use of elastic PE stored within tendons during the preparation phase. As the proximal limbs begin to move, the tendons of distal segments stretch as they lag behind, then recoil at significant speed because of their relatively low mass (Blazevich, 2017). Nonetheless, a throw-like pattern does not favour accuracy; therefore, beginners commonly rely on a cohesive push-like movement, counter-productive to power (Blazevich, 2017). Rather, to ensure optimal force production, as the player advances a throw-like pattern must be promoted.

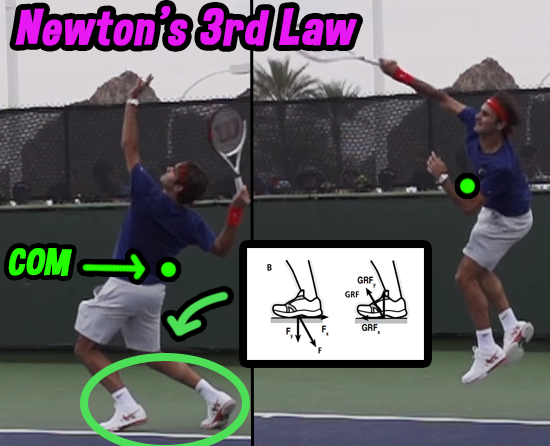

Furthermore, the acceleration phase relies upon COM and Newton’s Third Law, “[f]or every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction” (Blazevich, 2017, p. 45). Evident in Figure 8 as both an angular posterior-inferior impulse is produced and the player’s COM is manipulated, time over which torque can be applied increases (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011; Blazevich, 2017). Resultantly, the angular impulse applied also increases (τ.t), enhancing angular momentum under the proportional angular impulse-angular momentum relationship (Blazevich, 2017). Hence, Kovacs & Ellenbecker (2011) documented a small vertically directed impulse is often observed amongst professional players whilst player COM transitions anteriorly, increasing racquet height and subsequent torque generation.

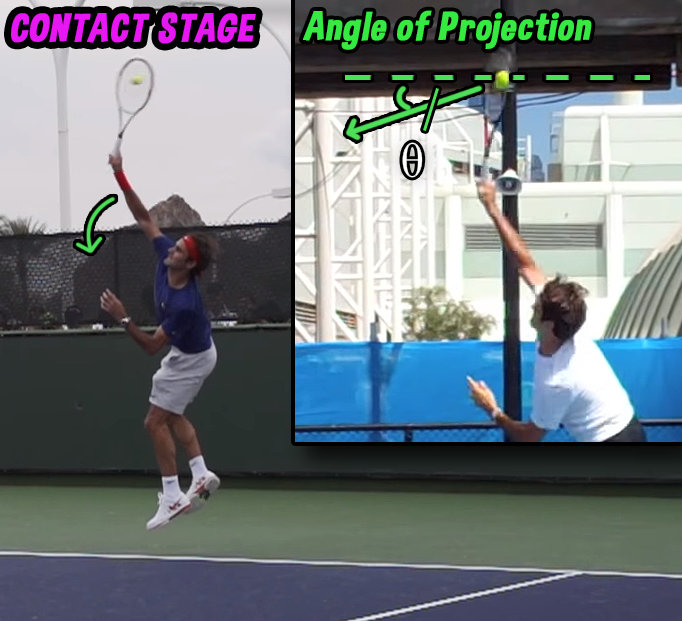

Contact stage:

The contact stage commences and ceases upon contact with the ball (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011). During this stage an unequal force imparted by the racquet acts on the ball, redirecting it under Newton’s First Law (Blazevich, 2017). Contact occurs at an angle of projection on or below the horizontal, aided by aptly displayed shoulder, elbow and wrist flexion, per Figure 9 (Fleisig, et al., 2003). Likewise, Whiteside, Elliott, Lay, & Reid (2013) found adult female professional players exhibited a mean projection angle of -6.8°, contrasting an angle of -5.4° amongst a cohort of 5 ranked, teenage players. This negative projection angle is a result of ball contact occurring at a positive relative height, with the tennis court lower than the contact point (Blazevich, 2017). Ultimately, the lower the projection angle the greater the horizontal velocity the tennis ball can exhibit, decreasing time of curvilinear flight, and resultant ball range (Blazevich, 2017). This was supported by Whiteside, et al. (2013), documenting female professional players exhibited an average horizontal ball velocity of 43.9 m.s-1, over 33.0 m.s-1 amongst the comparative. Nevertheless, optimal technique is largely reliant on intrinsic characteristics, such as height; however, if the ball is to exhibit a high horizontal velocity the angle of projection must be regulated, imparting force above the horizontal, relative to the height of contact.

Furthermore, the coefficient of restitution (CR) influences ball velocity following contact: “the proportion of total energy that remains with the colliding objects after the collision” (Blazevich, 2017, p. 117). Miller (2006) documented a tennis ball’s CR ranged from 0.75 to 0.7, suggesting 72.5% of kinetic energy is retained following contact with a rigid surface. However, this is even less during the serve, with CR inversely proportional to the velocity of tennis ball and racquet upon contact (Blazevich, 2017). Thus, the CR reaffirms the reliance of maximising horizontal velocity imparted on the ball and the dependence of the preparation phase, maximising KE within the system.

Additionally, the Magnus Effect causes the tennis ball to dip under imparted topspin (Mehta, Alam & Subic, 2008). As the ball passes through laminar or unobstructed fluid (air), drag force is subjected on the ball, dissipating energy as a boundary layer of air particles attaches, spinning with the ball (Blazevich, 2017). Figure 10 demonstrates the Magnus effect, evident as oncoming laminar flow is caught within this boundary layer, decreasing air speed and increasing pressure above the ball (Blazevich, 2017). In contrast the layer underneath the ball is unimpeded moving faster with the spin, decreasing the relative pressure, creating a pressure differential (Blazevich, 2017). This pressure differential causes the ball to swerve from high to low pressure, moving downwards (Blazevich, 2017). Nevertheless, Sakurai, et al. (2012) reported an inverse relationship between tennis ball spin rate and horizontal velocity, contrasting the average 1217rpm flat serve at 187.2km/h and the 3214rpm kick serve at 146.9km/h. Clearly, application of spin under the Magnus Effect is detrimental to ball speed, but can aid in diverting the ball’s trajectory downwards.