Start stage:

Within the preparation phase, the dynamic function is to store energy that is later transferred during the acceleration phase delivering powerful serve. Evident in Figure 1, a wide and stable base of support (BOS) is vital, as it allows for greater knee flexion whilst the centre of mass (COM) is retained within the BOS, facilitating the stable loading of the body (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011). Aligning the body with a stable BOS, will allow for greater force and power generation throughout the entire service motion (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011).

Release Stage:

The release stage is characterised through the release of the ball by the non-dominant hand, displayed by Roger Federer in Figure 2. Achieving a higher ball toss, allows the ball to gain both greater potential and kinetic energy, increasing the total energy output within the system (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011). The law of the conservation of energy states, “[t]he total energy within a system stays constant” (Blazevich, 2017, p. 104). Hence, a higher ball toss increases total energy output, resulting in a greater transfer of energy to the ball during contact (Blazevich, 2017). This is evidenced through a greater ball toss of 3.59m amongst professional players compared to 3.48m in amateur players, attributing to a 33.8 km/h speed difference between serves (Carboch, 2015). Potential energy, or energy relative (PE=mgh) is a product of mass, gravity and height, and hence directly proportional to peak ball height (h) (Blazevich, 2017). At peak height the ball’s trajectory begins to fall, gaining kinetic energy KE=1/2 mv2 (Blazevich, 2017). The higher the ball toss, the more PE it possesses and therefore the greater KE it gains as it falls, increasing the total energy of the system (Energy Total=KE+PE) (Blazevich, 2017). Therefore, a higher ball toss creates a significantly higher ball velocity following racquet contact (Carboch, 2015).

Loading Stage:

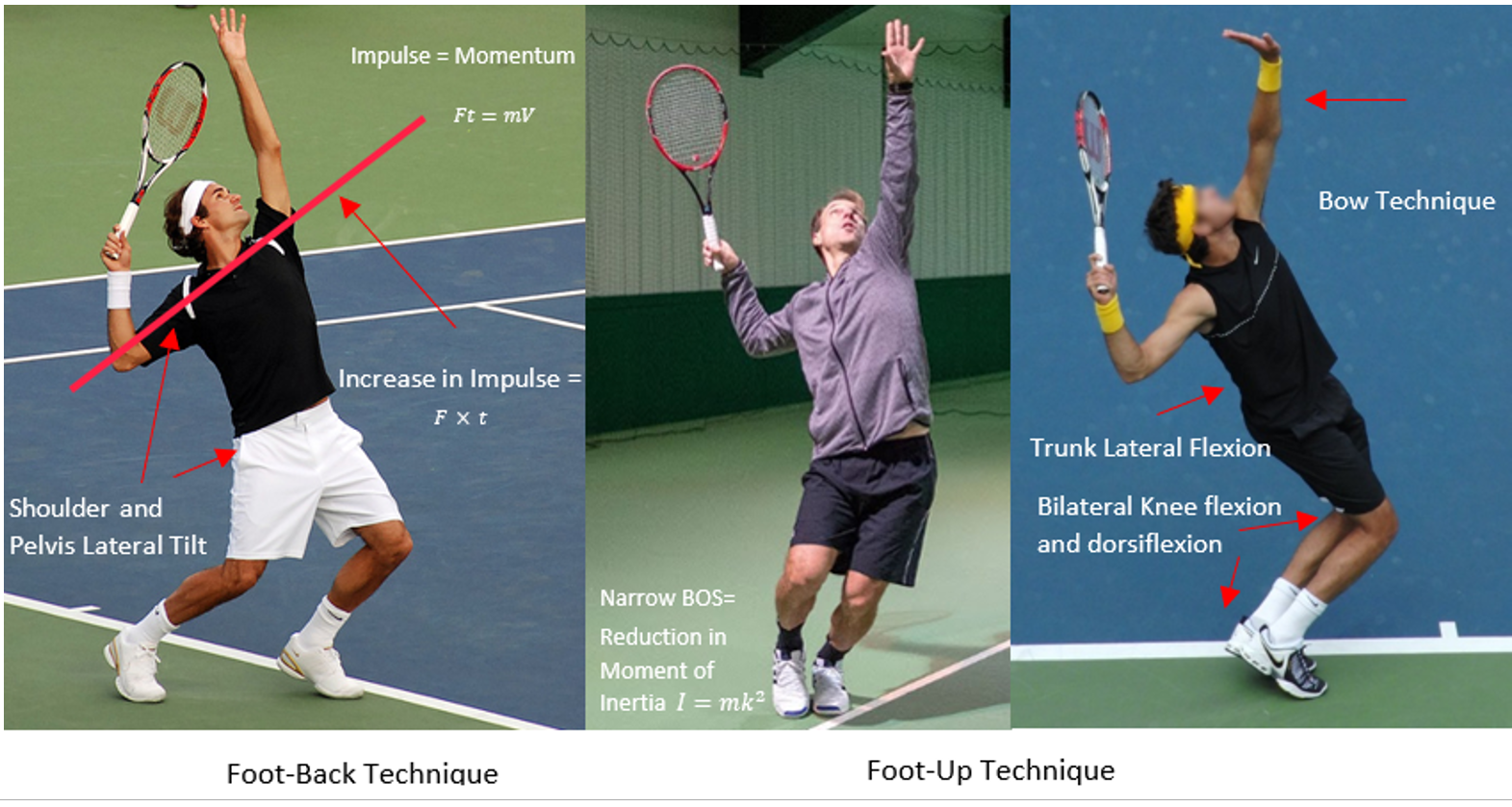

During the loading stage, the common “bow” technique shown in Figure 3 right, involves bilateral knee flexion and dorsiflexion, in combination with lateral flexion of the trunk and the cocking of the racquet arm (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011). Implementing this technique facilitates manipulation of the player’s COM, allowing greater time for the application of force during the acceleration phase (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011). Impulse (I=F.t) is a product of force and time, hence utilising the bow technique to manipulate COM, will increase force application over time and resultant impulse (Blazevich, 2017). The impulse-momentum relationship (I=p), indicates that an increase in impulse will directly correlate with an increase in momentum, allowing the racquet to achieve a higher velocity during the acceleration phase (Blazevich, 2017). Thus, during this motion lateral tilt of the pelvis and shoulder, exhibited by powerful servers, facilitates inferior and posterior movement of the COM, allowing for a greater impulse and higher velocity serve (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011).

Furthermore, this stage also involves two different feet techniques, foot-up and foot-back, to load the lower body, contrasted in Figure 3. Implementing the foot-up method, places both feet together, enabling the player to develop greater upward ground reaction forces to reach a greater height upon ball contact (Elliot & Wood, 1983; Martin, 2015). Martin et.al (2012) has shown professional players utilizing the foot-up technique generate on average, a higher service velocity (48.1 m.s-1 compared with 46.2 m.s-1). Utilizing a foot-up technique allows the BOS to become narrow, leading to forward rotation of the body towards the target, producing angular momentum (Martin, 2015). In addition, the narrow BOS allows the feet to be closer to the body, resulting in a decrease in moment of inertia (MOI), the propensity of the limb’s mass to resist changes in motion around an axis (Blazevich, 2017). MOI (I) = mk2, where m is the limb’s mass, and k, the radius of gyration, a coefficient for the distribution of mass from the axis of rotation. Decreasing the MOI by altering k, facilitates a greater angular velocity during rotation, allowing for enhanced transfer of velocity to the ball during contact, and a faster serve (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011).

Additionally, the foot-up method aids enhanced loading, with 11.4° less knee extension and subsequently increased storage of elastic PE within the tendons of the individual’s legs (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011). An increase in elastic energy, directly results in an increase in the amount of KE that is produced and transferred throughout the kinetic chain during the movement, resulting in a higher velocity at the distal upper limb (Blazevich, 2017).

Cocking Stage:

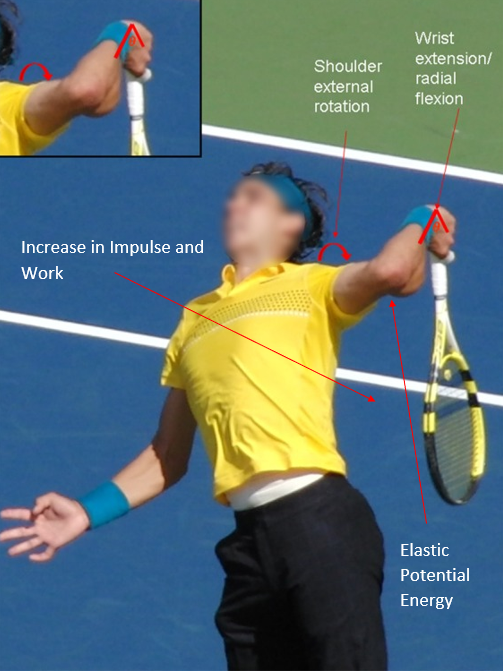

The cocking stage is characterised by the downward position of the racquet at maximal shoulder external rotation, highlighted in Figure 4 (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011). Driving the racquet behind the torso increases the time for force application, and consequently impulse, allowing for greater elastic PE, and application of work to the ball (Kovacs & Ellenbecker, 2011). Work is defined as force applied over distance (W=F.d); thus, as the racquet is cocked, the distance of force application and resultant work increases (Blazevich, 2017). Higher work is directly proportional to KE, resulting in greater angular momentum throughout the acceleration phase and a more powerful serve, as displayed by the power and energy relationship (P=KE/t) (Blazevich, 2017).